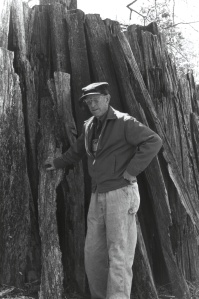

Lauchlin Shaw (1912-1999) was born on the Shaw homeplace, a two hundred-acre farm in the Anderson Creek township in southern Harnett County. Lauchlin’s great-grandfather Torquil Shaw acquired the land after emigrating from the Isle of Jura on the southwestern coast of Scotland around 1825. Eastern North Carolina was the destination for Scottish Highlanders prior to the Civil War and many settled in the Cape Fear River valley. Torquil spoke Gaelic and passed the language, as well as other customs and beliefs, to his children and grandchildren.

Lauchlin Shaw (1912-1999) was born on the Shaw homeplace, a two hundred-acre farm in the Anderson Creek township in southern Harnett County. Lauchlin’s great-grandfather Torquil Shaw acquired the land after emigrating from the Isle of Jura on the southwestern coast of Scotland around 1825. Eastern North Carolina was the destination for Scottish Highlanders prior to the Civil War and many settled in the Cape Fear River valley. Torquil spoke Gaelic and passed the language, as well as other customs and beliefs, to his children and grandchildren.

It is not known whether Torquil played a fiddle. However, family stories say that Torquil’s son, Gilbert, could fiddle. Gilbert’s son, Archibald Alexander, read shape notes and taught singing schools. Together with his brother Colin, who played both fiddle and banjo, Archibald provided music at square dances. Archie’s son Lauchlin heard his father fiddle “a lot of old hoedowns, like ‘Soldiers Joy,’ and ‘Mississippi Sawyer’ and ‘Sally With the Run-Down Shoes.’ ” Lauchlin remembered that the instrumentation at dances was often fiddle and banjo, though sometimes Colin played lead on the fiddle with his brother Archie, who possessed a good ear for harmony, adding a “second.”

Archie Shaw married Mary Berta Nordan in 1895. The couple raised seven sons and five daughters. Most of the boys played fiddle, banjo or guitar and the girls played organ and sang. Lauchlin, the ninth child, started on the banjo and then took up the fiddle. Possessing a remarkable memory and an excellent ear, he learned many of the tunes played by his father, his uncle Colin, and his older brothers. By the time he began fiddling at dances in the mid-1920s, Lauchlin already knew a number of breakdowns and waltzes. He inherited his father’s sense of harmony and could play a second to most of the pieces in his repertory.

Lauchlin recalled that in his youth, dances were held “during Christmas and New Years. Almost every night for a week or so. Then it would wane off until sometime later. Then we’d would play here (at home) a lot of times and neighbors would come in and listen to it.” The Shaw family band also played regularly in a hotel in the nearby town of Lillington and once for a dance following a fox hunt at the nearby country retreat of the Rockefeller family of New York. Each band member received a five dollar gold piece in compensation for his efforts.

In addition to learning from immediate family, Lauchlin acquired tunes from local fiddlers. Brothers Henry and Will Faucett of Lillington, Sampson Williams of Dunn, Lauchlin Bethune from Bunnlevel, Percy Clifton of Benson, Frank Nordan from Hope Mills and John McArthur Godwin from Erwin were all gifted musicians whom he would meet at fiddlers conventions, dances and other social gatherings.

After his parents died, Lauchlin gave up his job in a local cotton mill, bought out his siblings’ shares in the family homeplace and began his career as a farmer. He married Mary Lily Foard in 1943 and the couple had three daughters. With family and farm responsibilities, Lauchlin made music a much lower priority.

After his daughters were grown, he began to venture out again to fiddlers conventions and to make music on a regular basis with regional musicians such as Virgil Craven, Fred Olson, Marvin Gaster, A.C. Overton and Wade Yates. In the 1970s Lauchlin and Mary Lilly started hosting jam sessions in which musicians young and old participated. During this period their daughter Evelyn became serious about fiddling. Learning from her father brought the two closer and enabled the family tradition to extend another generation.

Lauchlin had pride in his Highland Scots heritage and wondered whether the tunes he played had direct links to Scotland. Indeed, some tunes learned from his father—such as Leather Britches (Lord MacDonalds Reel), Hop Light Ladies (McCloud’s Reel) and Soldiers Joy have roots in the British Isles. However, these are fairly common tunes that Southern fiddlers of all backgrounds play. Also, these pieces were only a small part of his repertory. Even if Lauchlin’s Scottish ancestors brought fiddling to the Cape Fear River Valley, it is safe to say that the fiddle and banjo ensemble tradition, born in America from African and European cultural interchange, had become the dominant influence on repertory in the Piedmont by the last third of the nineteenth century.

That Lauchlin’s bowing style had a deeper connection to the British Isles is a more tantalizing conjecture. He was adept at both pulling and pushing the bow but favored a bowing pattern in which bow upstrokes were often achieved using a circular motion of the wrist. This bowing style imbued his playing with a propulsive energy that was well suited for flatfoot and square dancing. Smith McInnis, whose ancestors also emigrated from Scotland, employed a similar bowing style that used a rolling wrist to push the bow forward. Whether this is merely a coincidence or indicative of an older bowing pattern handed down from early Scottish settlers in the Cape Fear River Valley is a mystery.

As Lauchlin’s musical reputation spread, he received many invitations to share his music with audiences beyond Harnett County. He was a featured performer at festivals including the Festival of American Fiddle Tunes in the state of Washington and the Tennessee Banjo Institute. In 1992 he received North Carolina’s Folk Heritage Award. Lauchlin’s fiddle playing is documented on the CD, Sally With the Run-Down Shoes, issued on the Merimac label and on an anthology of North Carolina piedmont stringband music entitled Going Down to Raleigh.